The New York Times

By PETER S. GOODMAN

Published: March 2, 2008

OAKLAND, Calif. — NICOLE FLENNAUGH has a college degree, office experience and the modest expectation that, somewhere in this city on the eastern lip of San Francisco Bay, someone will want to hire her.

Nicole Flennaugh, a college graduate, has had a difficult time finding a full-time job nearly two years after she was laid off as a customer service representative.

Greg Bailey of Oakland enrolled in a biotech training program, but he has not been able to find a job in the industry.

But Ms. Flennaugh, 36, a widow, cannot secure steady, decent-paying work to support herself and her two daughters. Nearly two years after she was laid off as a customer service representative at the Educational Testing Service, and even after applying for dozens of full-time jobs, she has been getting by with occasional stints as an office temp.

“You’re used to making $17 an hour with benefits, and now you have to take any job for $8 an hour,” Ms. Flennaugh says. On a recent afternoon, she sat in front of a computer terminal at an employment center in a gritty part of town, scrolling dejectedly through online job listings while sending another batch of applications into the ether.

“I’ve literally sat and cried, but my friends with double degrees are doing worse,” she says. “It’s the economy. It’s really bad.”

Now, it’s getting tougher — particularly for those at the lower rungs of the economic ladder, and especially for African-Americans like Ms. Flennaugh. As the economy slows and perhaps slides deeper into a recession that may already be under way, communities like this — cities that have long struggled with a shortage of jobs — see work becoming scarcer still.

Across the nation, the labor market has been deteriorating. Many companies, long reluctant to add workers, are hunkered down and waiting for improved prospects, engaged in what Ed McKelvey, a senior economist at Goldman Sachs, calls “a hiring strike.” Americans with jobs are taking cuts to their work hours; those without jobs are staying out of work longer, or accepting positions that pay far less than they earned previously.

Teenagers are struggling to land minimum-wage jobs at fast-food restaurants, because those positions are increasingly being filled by adults. And those with poor credit are finding that this can disqualify them from getting a job.

IN many communities, dreams of upward mobility are yielding to despair and the grim realization that the economy — not strong for less-educated workers even when it was growing — may now be shrinking, making it tougher than ever to find a job.

Indeed, the increasingly anemic job market comes on the heels of six years of economic expansion that delivered robust corporate profits but scant job growth. The last recession, in 2001, was followed by a so-called jobless recovery. As the economy resumed growing, payrolls continued to shrink.

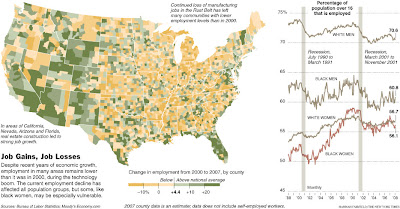

Even as job growth accelerated in 2005 and 2006 before slowing last year, it was not enough to return the country to its previous level. Some 62.8 percent of all Americans age 16 and older were employed at the end of last year, down from the peak of 64.6 percent in early 2000, according to the Labor Department.

“The economy never got its groove back after the tech bubble burst,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Economy.com. “We’re still feeling fallout from the collapse of the tech economy and the accounting scandals. There are still psychological scars for the managers affected. Managers are less interested in taking risks.”

In many metropolitan areas, overall employment remains below levels reached before the last recession; the list includes New York, Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee and Buffalo, as well as Boulder, Colo.; Spartanburg, S.C.; and Topeka, Kan., according to Economy.com.

Please click on image to enlarge to read...

As the presidential contenders Hillary Rodham Clinton and Barack Obama crisscross Ohio ahead of its Democratic primary on Tuesday, they are stopping in many cities on that list — Canton, Cleveland, Dayton, Toledo. They are focusing on bread-and-butter economic issues, promising to increase the minimum wage, extend unemployment benefits and generate new jobs.

Oakland, long known as the blue-collar sibling to the aristocratic San Francisco across the bay, is among the metropolitan areas that never fully recovered from the last recession, with fewer jobs today than in March 2001, according to Economy.com. The technology boom of the 1990s and the real estate bonanza of more recent years created fewer jobs and less wealth here than they did in the moneyed enclaves like Silicon Valley. Yet if Oakland missed out on the festivities, it is already feeling the pullback.

“There’s more competition for every job,” said Gay Plair Cobb, chief executive of the Oakland Private Industry Council, a job training organization. “People are getting discouraged and depressed.”

Home to about 400,000 people, Oakland is enormously diverse, with blacks making up 36 percent of the population, Hispanics 22 percent and Asian-Americans 15 percent, according to the 2000 census. The city is racked by stubborn poverty, with one-fifth of all households living on less than $15,000 in annual income, according to the census.

Given that picture, Oakland reflects a national trend: The weaker labor market is especially pronounced for African-Americans, and black women in particular, a slide that has halted a quarter-century of steady gains.

From 1975 to early 2000, the percentage of African-American women who were employed jumped to 59 percent from 42 percent. Two years later, following a recession, the percentage had dropped to 55 percent. Since then, employment among African-American women has shown little change, reaching 55.7 percent at the end of 2007.

In a recent paper, the Center for Economic and Policy Research asserted that a recession in 2008 would be likely to swell the ranks of the unemployed by 3.2 million to 5.8 million, while raising the unemployment rate among black Americans to 11.3 percent to 15.5 percent, compared with 8.3 percent in 2007.

Nationally, the unemployment rate remains at a historically low level of 4.9 percent, though this does not include people who have given up looking for work.

The slide in employment is occurring at a time when jobs are more important than ever for millions of households headed by African-American women, because welfare changes in the 1990s forced many into the job market to compensate for a loss of public assistance.

“The labor market for low-income women is so poor that it’s almost a hoax,” says Randy Albelda, an economist at the University of Massachusetts in Boston.

For more than a decade, Dorothy Thomas, 49, an African-American and a mother of two, worked as an administrative assistant at various health care centers in Northern California. In her last job, she earned $16 an hour, as well as benefits, she said.

It was never enough to pay all the bills, she said, so she made choices, paying this one, not paying that one, all the while focused on one mission: getting her two daughters through school. She lived in apartments in better neighborhoods, paying more rent than she could afford to ensure that her girls attended better schools.

“I truly bought into the idea that education is the way out of poverty,” Ms. Thomas says. One daughter received a master’s degree in education and is a teacher in Hawaii, she says, and the other is still in college.

But the bills for Ms. Thomas are still coming due. She lost her car in November 2005 after she fell behind on the payments. Unable to drive to work, she lost her job. Since then, she has been unable to find a job.

Several times, she has landed interviews that seemed likely to bring offers, but the jobs required a credit check — a test she cannot pass.

“My credit is just so in shambles,” she told a classroom full of people gathered for a credit counseling session at the Private Industry Council. “More and more jobs are checking your credit. They’re saying that credit is a reflection of your character.”

Ms. Thomas deftly toggles between different modes of speech, from street-smart to receptionist-smooth. But getting to work without transportation and buying clothes for interviews without cash are beyond her abilities.

“Why can’t I get a job?” she asks, her eyes welling with tears. “Is it because of my age? Is it because I’ve gained weight? I’m articulate. I’m a positive thinker. I know how to conduct myself in an office setting. But I’m starting to lose all my confidence.”

Government data show that the labor market has weakened in recent years for nearly every demographic group. Women as well as men; whites, blacks, Hispanics and Asian-Americans; teenagers and the middle-aged; high school graduates and those with college degrees. In terms of employment as a percentage of population, all remain below the level reached before the last recession.

The source of this weakening and what it says about the overall, long-term health of the economy are the subject of fractious debate.

Some economists argue that the labor market has merely settled back to earth after years of ridiculously aggressive investment in technology, which created far more jobs in the 1990s than could be sustained.

“This is a return to normal,” says Robert E. Hall, an economist and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, a conservative research group at Stanford.

But others conclude that the sluggish job market reflects long-term, systemic forces reshaping the American economy. It represents, they say, the underbelly of the so-called new moderation that has made recessions less frequent and less severe.

Traditionally, the American economy has often expanded in extreme cycles. In periods of growth, companies hire aggressively. When they sense a slowdown, they cut back, laying off workers and curtailing investments, amplifying the ripples of retrenchment. Now, however, companies aim to keep their work forces lean all the time.

AS the American economy boomed in the late 1990s, so did business for the Bartlett Manufacturing Company, a circuit-board maker based in Cary, Ill. By 2000, it had about 200 workers — mostly in blue-collar assembly jobs at its original factory near Chicago, and an additional 50 or so at a new plant in Albuquerque, said the company’s chairman, Douglas S. Bartlett. Most of the positions paid $10 to $11 an hour.

But by late 2001, with the country in recession and many orders flowing to China, business was down two-thirds from the best years. So the company shuttered its Albuquerque factory and laid off more than 100 workers at its Chicago plant, bringing its total work force down to 87.

Business improved slightly in 2004 and 2005 and remained essentially flat over the last two years, but the company hasn’t added workers.

“We improved our process through automation,” Mr. Bartlett says.

If business now deteriorates, he does not expect to shed workers, because he is already down to the minimum needed to keep his plant running.

“When a customer calls, you need to be able to deliver parts in three or four days because, if they could wait longer, they would just go offshore and get it cheaper,” Mr. Bartlett says. “We don’t lay people off at this point. We just reduce hours. We pretty much can’t get any leaner.”

Bartlett Manufacturing’s experience is emblematic of forces at work throughout the economy. An anemic job market is not so much a product of layoffs — which remain relatively few — as it is a result of a sharp pullback in hiring.

In 1994, 30 million people were hired into new and existing private-sector jobs, according to the Labor Department. By 2000, the number of hires had expanded to 34 million. A year later, in the midst of the recession, hiring slackened to 31.6 million, while layoffs winnowed the work force.

In 2003, with the economy again growing, layoffs slowed, but the private sector hired only 29.8 million — a figure that has nudged up only a little in the years since.

Rather than hire and risk having to fire in another downturn, companies added hours for those already on the payroll and relied more on temporary workers, said Mr. McKelvey, the Goldman Sachs economist. Manufacturing companies continued to automate, to squeeze more production out of the same number of workers, while shifting jobs to lower-cost countries like China and Mexico. For lower-skilled workers, that intensifies the competition for the jobs that remain.

“Now, you’re not only competing against the guy next door,” Mr. McKelvey says. “You’re competing against the guy across the water.”

Some economists say the weakness of hiring in recent years may protect those with jobs against the usual impact of a recession: Many companies are so lean that the unemployment rate may not increase much.

“It’s not your grandfather’s recession anymore,” says Jared Bernstein, senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute, a labor-oriented research group in Washington. “You’re probably going to see fewer layoffs, because you just don’t have the traditional model.”

But the same trend suggests that the impacts of the slowdown are likely to be felt deeply for several years, even after the economy resumes a swift expansion, Mr. Bernstein added.

Before 1990, it took an average of 21 months for the economy to add back the jobs shed during a recession, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute and the National Employment Law Project, a worker advocacy group. Yet in the last two recessions, in 1990 and 2001, it took 31 months and 46 months, respectively, for employment levels to recover fully.

In the recessions of the early 1980s and the early 1990s, the ranks of the so-called long-term unemployed — those out of work for 27 weeks or more — jumped to well above 20 percent of all unemployed people. But in both cases, that share eventually settled back to close to 10 percent of the unemployed.

After the 2001 recession, however, the long-term share stayed above 20 percent from the fall of 2002 until the spring of 2005. In the months since, it has never dipped below 16 percent. In January, 18 percent of those unemployed had been without work for at least 27 weeks, according to the Labor Department.

OAKLAND is typical of the lean hiring that has accompanied the winnowing of jobs. In recent decades, Oakland’s once-formidable manufacturing base has hollowed out as the city has lost food processing factories, auto plants and warehouses. Downtown, concrete-floor factories have been turned into chic residential loft spaces.

Yet the Port of Oakland is booming, with dozens of cranes arrayed at the bay’s edge, plucking containers full of cars and electronic products off of ships arriving from Asia, and depositing shipments of produce from the Central Valley of California.

The port has benefited from a surge in American exports. Port officials cite an economic development study showing that jobs connected in some way to their operations — in industries ranging from cargo and trucking to insurance and retail — doubled to more than 28,000 from 2001 to 2005. A planned $800 million expansion would add 7,000 more jobs, said James Kwon, director of the port’s maritime division.

Deborah Acosta, international trade project manager of the Community and Economic Development Agency of Oakland, says, “We’re talking about good-paying jobs that don’t require a college degree.”

So far, the growth at the port has not been enough to compensate for steady erosion of work elsewhere in the city. Since 2001, the metropolitan area has shed 22,000 manufacturing jobs, and thousands more in transportation and warehousing, and professional and business services, according to Economy.com.

For public officials grappling with the social and political impact of long-term joblessness, training has become a mantra.

“The jobs are there, but the people to fill the jobs are not,” says John Garamendi, the lieutenant governor of California. “The current demand for skilled individuals in medical fields, in biotech, for people capable of welding — there’s a demand for these people.”

But all too often, these job-training programs fail to find people the jobs they expect, said Marsha Murrington, vice president for programs at the Unity Council, a nonprofit social service organization that operates a job center in Oakland.

“People are getting training or high degrees in areas that are not supported by the job market,” she complains. “People are looking for those high-paying corporate jobs that aren’t there.”

Greg Bailey, another Oakland resident, is among those who banked on the benefits of job training. Last spring, after 15 years as a truck driver, an installer of household appliances and a warehouse stocker — jobs that left him nursing a bad back and high blood pressure — Mr. Bailey decided to pursue work that was less physically taxing. He enrolled in a government-financed training program to gain the skills needed to work at one of the many biotechnology plants sprouting up in the area.

“It sounded great; the opportunities were almost endless,” said Mr. Bailey, 40, tall, soft-spoken and personable.

A former high school basketball star, Mr. Bailey said he had to turn down several college scholarships when he graduated so he could find a job and support his mother, who was ill, along with his younger brother. Later, he enrolled several times in various college programs, but the demands of being the family’s primary breadwinner left too few hours for schoolwork.

The biotech training program was to be a way to jump ahead, putting him in position to earn $17 to $18 an hour, as well as health benefits, as a warehouse or maintenance worker in an industry that offered other chances for advancement. But despite applying for about 100 jobs over the last six months, he says, he has never been invited to an interview.

Last summer, a month after the course ended, he went to a job center in East Oakland and was surprised to bump into six of his classmates.

“I was like, ‘Oh man, you’re all here too?’ ” Mr. Bailey said. “We all started looking at anything at that point. It was kind of depressing.”

RECENTLY, he began applying for the same types of jobs from which he had hoped to escape. Now, even those jobs seem beyond reach. He did take one warehouse job that started at 5 a.m. and required him to walk two miles to and from work, but he quit in disgust after two weeks. It paid $10 an hour — two-thirds of what he used to make as a truck driver.

He applied for a minimum-wage job at Wal-Mart, but after two interviews the person doing the hiring was fired, he said, and Mr. Bailey was told that he had to start all over — this for a night shift at a store in an area plagued by crime. Disenchanted, he stopped pursuing a career at Wal-Mart.

“I’ll just look for anything now; it doesn’t matter,” he confided on a recent afternoon.

The next day, he accepted a job at a warehouse for $9 an hour.

“It’s just picking up boxes,” he says. “That’s all right. I’ve got to do something.”