Sunday, March 9, 2008

Seeing an End to the Good Times (Such as They Were)

Seeing an End to the Good Times (Such as They Were)

By David Leonhardt

The New York Times

March 8, 2008

If history is a reliable guide, the recession of 2008

is now unavoidable.

The dismal jobs report released Friday showed overall

employment to be lower than it was three months ago.

Every time such a slump has occurred since the early

1970s, a recession has followed - or already been under

way.

And if the good times have really ended, they were

never that good to begin with. Most American households

are still not earning as much annually as they did in

1999, once inflation is taken into account. Since the

Census Bureau began keeping records in the 1960s, a

prolonged expansion has never ended without household

income having set a new record.

For months, policy makers and Wall Street economists

have been predicting, and hoping, that the aggressive

series of interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve

would keep the economy growing, despite the housing

bust. But the possibility seemed to diminish almost by

the hour on Friday.

Shortly after 8 a.m., the Fed announced yet another

measure meant to unlock the struggling credit markets.

At 8:30, the Labor Department released the unexpectedly

poor jobs report. Almost immediately, the economists at

JPMorgan Chase - who only last week had told clients

they thought the economy was still growing - reversed

course and said a recession appeared to have started

earlier this year.

Stocks fell when the markets opened at 9:30, recovered

and then fell again, with the Standard & Poor 500-stock

index closing down 0.8 percent. Traders became even

more confident, based on the price of futures

contracts, that the Fed would cut its benchmark

interest rate three-quarters of a point, to 2.25

percent, when policy makers meet on March 18.

'The question was always, ˜Would the economy hang on by

its fingernails?' ' said Ethan Harris, the chief United

States economist at Lehman Brothers. Based on the

employment report, Mr. Harris said, 'there's a very

high probability that we're in a recession now.'

Even the one apparent piece of good news in the

employment report was a mirage. The unemployment rate

fell to 4.8 percent, from 4.9 percent in January, but

only because more people stopped looking for work and

thus were not counted as unemployed by the government.

Over the last year, the number of officially unemployed

has risen by 500,000, while the number of people

outside the labor force - neither working nor looking

for a job - has risen by 1.3 million.

Employment has risen by 100,000, but even that comes

with a caveat: there are also 600,000 more people who

are working part time because they could not find full-

time work, according to the Labor Department.

'The decline in the unemployment rate,' said Joshua

Shapiro, an economist at MFR, a research firm in New

York, 'should not be viewed as good news.'

Much of the economic stimulus put in place by the

government will begin to take effect in the next few

months, which does leave open the possibility that the

country can still escape a recession. Policy makers

have reacted quite quickly to this slowdown, relative

to previous ones.

The Treasury Department will begin sending out rebate

checks - of up to $1,200 for couples, plus $300 per

child - in May, as part of the stimulus package

negotiated by President Bush and Democratic leaders in

Congress. The Fed has already cut its benchmark short-

term interest rate five times since September, and such

reductions typically take six months or more to wash

through the economy.

White House officials have predicted in recent weeks

that the economy would avoid recession, but after the

release of the jobs report, they offered a subtly

different forecast. At the White House on Friday,

Edward P. Lazear, the chairman of Mr. Bush's Council of

Economic Advisers, parried reporters' questions about

whether he now thought the economy would slip into a

recession.

Instead, he said, 'I'm still not saying that there is a

recession.'

The administration does expect growth in the current

quarter to be slower than it had previously thought,

before accelerating this summer. 'Obviously, we are

concerned,' Mr. Lazear said. But he added that he

remained hopeful that 'growth will pick up, and pick up

quickly.'

The most commonly cited arbiter of recessions is the

National Bureau of Economic Research, a group of

academic economists that is based in Cambridge, Mass.

(Mr. Lazear referred to the group at his briefing,

saying it would not be clear whether there had been a

recession until the bureau had made an announcement.)

The seven economists who sit on the bureau's recession-

dating committee began exchanging e-mail messages late

last year about whether the economy was on the verge of

a recession. But committee members said Friday that it

remained too early to know.

The bureau defines a recession as a significant,

protracted decline in activity that cuts across the

economy, affecting measures like income, employment,

retail sales and industrial production.

'Given that definition, the committee can't possibly

call a recession until it has been going on for a

while,' said Christina D. Romer, an economics professor

at the University of California, Berkeley. 'There is no

way to know if the downturn will be sufficiently long-

lasting until it has lasted for a while.'

The committee did not announce the end of the last

recession - which came in November 2001 - until more

than a year-and a half later. Robert J. Gordon, a

Northwestern University economist on the committee,

said any announcement about the start of a new

recession was unlikely before the last few months of

2008 at the earliest.

Recent recessions have inevitably brought inflation-

adjusted income declines for most families, which would

be particularly painful given what has happened over

the last decade. For a variety of reasons that

economists only partly understand - including

technological change and global trade - many workers

have received only modest raises in recent years,

despite healthy economic growth.

The median household earned $48,201 in 2006, down from

$49,244 in 1999, according to the Census Bureau. It now

looks as if a full decade may pass before most

Americans receive a raise.

By David Leonhardt

The New York Times

March 8, 2008

If history is a reliable guide, the recession of 2008

is now unavoidable.

The dismal jobs report released Friday showed overall

employment to be lower than it was three months ago.

Every time such a slump has occurred since the early

1970s, a recession has followed - or already been under

way.

And if the good times have really ended, they were

never that good to begin with. Most American households

are still not earning as much annually as they did in

1999, once inflation is taken into account. Since the

Census Bureau began keeping records in the 1960s, a

prolonged expansion has never ended without household

income having set a new record.

For months, policy makers and Wall Street economists

have been predicting, and hoping, that the aggressive

series of interest rate cuts by the Federal Reserve

would keep the economy growing, despite the housing

bust. But the possibility seemed to diminish almost by

the hour on Friday.

Shortly after 8 a.m., the Fed announced yet another

measure meant to unlock the struggling credit markets.

At 8:30, the Labor Department released the unexpectedly

poor jobs report. Almost immediately, the economists at

JPMorgan Chase - who only last week had told clients

they thought the economy was still growing - reversed

course and said a recession appeared to have started

earlier this year.

Stocks fell when the markets opened at 9:30, recovered

and then fell again, with the Standard & Poor 500-stock

index closing down 0.8 percent. Traders became even

more confident, based on the price of futures

contracts, that the Fed would cut its benchmark

interest rate three-quarters of a point, to 2.25

percent, when policy makers meet on March 18.

'The question was always, ˜Would the economy hang on by

its fingernails?' ' said Ethan Harris, the chief United

States economist at Lehman Brothers. Based on the

employment report, Mr. Harris said, 'there's a very

high probability that we're in a recession now.'

Even the one apparent piece of good news in the

employment report was a mirage. The unemployment rate

fell to 4.8 percent, from 4.9 percent in January, but

only because more people stopped looking for work and

thus were not counted as unemployed by the government.

Over the last year, the number of officially unemployed

has risen by 500,000, while the number of people

outside the labor force - neither working nor looking

for a job - has risen by 1.3 million.

Employment has risen by 100,000, but even that comes

with a caveat: there are also 600,000 more people who

are working part time because they could not find full-

time work, according to the Labor Department.

'The decline in the unemployment rate,' said Joshua

Shapiro, an economist at MFR, a research firm in New

York, 'should not be viewed as good news.'

Much of the economic stimulus put in place by the

government will begin to take effect in the next few

months, which does leave open the possibility that the

country can still escape a recession. Policy makers

have reacted quite quickly to this slowdown, relative

to previous ones.

The Treasury Department will begin sending out rebate

checks - of up to $1,200 for couples, plus $300 per

child - in May, as part of the stimulus package

negotiated by President Bush and Democratic leaders in

Congress. The Fed has already cut its benchmark short-

term interest rate five times since September, and such

reductions typically take six months or more to wash

through the economy.

White House officials have predicted in recent weeks

that the economy would avoid recession, but after the

release of the jobs report, they offered a subtly

different forecast. At the White House on Friday,

Edward P. Lazear, the chairman of Mr. Bush's Council of

Economic Advisers, parried reporters' questions about

whether he now thought the economy would slip into a

recession.

Instead, he said, 'I'm still not saying that there is a

recession.'

The administration does expect growth in the current

quarter to be slower than it had previously thought,

before accelerating this summer. 'Obviously, we are

concerned,' Mr. Lazear said. But he added that he

remained hopeful that 'growth will pick up, and pick up

quickly.'

The most commonly cited arbiter of recessions is the

National Bureau of Economic Research, a group of

academic economists that is based in Cambridge, Mass.

(Mr. Lazear referred to the group at his briefing,

saying it would not be clear whether there had been a

recession until the bureau had made an announcement.)

The seven economists who sit on the bureau's recession-

dating committee began exchanging e-mail messages late

last year about whether the economy was on the verge of

a recession. But committee members said Friday that it

remained too early to know.

The bureau defines a recession as a significant,

protracted decline in activity that cuts across the

economy, affecting measures like income, employment,

retail sales and industrial production.

'Given that definition, the committee can't possibly

call a recession until it has been going on for a

while,' said Christina D. Romer, an economics professor

at the University of California, Berkeley. 'There is no

way to know if the downturn will be sufficiently long-

lasting until it has lasted for a while.'

The committee did not announce the end of the last

recession - which came in November 2001 - until more

than a year-and a half later. Robert J. Gordon, a

Northwestern University economist on the committee,

said any announcement about the start of a new

recession was unlikely before the last few months of

2008 at the earliest.

Recent recessions have inevitably brought inflation-

adjusted income declines for most families, which would

be particularly painful given what has happened over

the last decade. For a variety of reasons that

economists only partly understand - including

technological change and global trade - many workers

have received only modest raises in recent years,

despite healthy economic growth.

The median household earned $48,201 in 2006, down from

$49,244 in 1999, according to the Census Bureau. It now

looks as if a full decade may pass before most

Americans receive a raise.

Friday, March 7, 2008

Employers slash jobs by most in 5 years

But, wait! George Bush says the economy is okay... no problems as he can see except a few extra homes were built. According to Bush his war spending is helping people keep busy working... why do all the economic stories tell a different story from George Bush?

Employers slash jobs by most in 5 years

By JEANNINE AVERSA, AP Economics Writer

Employers slashed 63,000 jobs in February, the most in five years and the starkest sign yet that the country is heading dangerously toward recession or is in one already.

The Labor Department's report, released Friday, also indicated that the nation's unemployment rate dipped to 4.8 percent as hundreds of thousands of people ? perhaps discouraged by their prospects ? left the civilian labor force. The jobless rate was 4.9 percent in January.

Job losses were widespread, with hefty cuts coming from construction, manufacturing, retailing, financial services and a variety of professional and business services. Those losses swamped gains elsewhere, including education and health care, leisure and hospitality and the government.

The latest snapshot of the nation's employment climate underscored the heavy toll of the housing and credit crises on companies, jobseekers and the overall economy.

To provide relief to persistent credit problems, the Federal Reserve announced Friday that it will increase the amount of loans it plans to make available to banks this month to $100 billion.

It has already provided a total of $160 billion in short-term loans to cash-strapped banks since the auctions began in December. The Fed's new step will involve making $100 billion available to a broad range of financial players through a series of separate transactions.

On Wall Street, the Dow Jones industrials were off around 15 points in morning trading as the Fed's actions helped to blunt worry about the eroding jobs situation.

The Labor report also showed that January's job losses were worse than the government first reported. Employers cut 22,000 jobs, versus 17,000.

It was the first monthly back-to-back job losses since May and June 2003, when the job market was still struggling to recover from the blows of the 2001 recession.

The health of the nation's job market is a critical factor shaping how the overall economy fares. If companies continue to cut back on hiring, that will spell more trouble.

"It certainly solidifies the notion that the economy has fallen into a recession," said Ken Mayland, economist at ClearView Economics.

Friday's report was much weaker than economists were expecting. They were forecasting employers to boost payrolls by around 25,000. However, they were also expecting the jobless rate to edge up to 5 percent. The reason why the jobless rate went down, rather than up, is because so many people stopped looking for work and left the labor force.

"We are disappointed any time you see a number showing lost jobs," Commerce Secretary Carlos Gutierrez told The Associated Press. "This is consistent with a slowdown," he said. Still, he was hopeful that the recently enacted economic stimulus package forged by the White House and Congress will help bolster the economy in the second half of this year.

Workers with jobs, however, saw modest wage gains.

Average hourly earnings for jobholders rose to $17.80 in February, a 0.3 percent increase from the previous month. That was on target with economists' forecasts. Over the last 12 months, wages were up 3.7 percent. With high energy and food prices, though, workers may feel squeezed and feel like their paychecks aren't stretching that far.

With the economy losing momentum, fears have grown that the country in on the brink of its first recession since 2001.

Economic growth slowed to a near standstill of just a 0.6 percent pace in the final quarter of last year. Many economists predict growth in the January-to-March quarter will be worse, around a 0.4 percent pace. Some believe the economy is shrinking now.

Spreading fallout from the housing and credit debacles are the main factors behind the economic slowdown. People and businesses alike are feeling the strains and have turned cautious. Adding to the stresses on pocketbooks, budgets and the economy: skyrocketing energy prices. Oil prices have set a string of record highs in recent days. Gasoline prices have marched higher, too.

To help shore up the economy, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke signaled last week that the central bank is prepared to lower interest rates again. Economists predict another cut on March 18, the Fed's next meeting. The Fed, which has been slicing the rate since September, recently turned more forceful. It slashed the rate by 1.25 percentage points in the course of just eight days in January ? the biggest one-month reduction in a quarter century.

The White House and Congress, meanwhile, speedily enacted an economic relief package, including tax rebates for people and tax breaks for businesses. That ? along with the Fed's rate cuts ? should help give a lift to the economy in the second half of this year, says Bernanke.

Still, unemployment is expected to move higher this year. The Federal Reserve predict the jobless rate will rise to as high as 5.3 percent in 2008. Last year, the unemployment rate averaged 4.6 percent.

All the economy's troubles are putting people in a gloomy mood.

According to the RBC Cash Index, confidence sank to a mark of 33.1 in early March, the worst reading since the index began in 2002.

Employers slash jobs by most in 5 years

By JEANNINE AVERSA, AP Economics Writer

Employers slashed 63,000 jobs in February, the most in five years and the starkest sign yet that the country is heading dangerously toward recession or is in one already.

The Labor Department's report, released Friday, also indicated that the nation's unemployment rate dipped to 4.8 percent as hundreds of thousands of people ? perhaps discouraged by their prospects ? left the civilian labor force. The jobless rate was 4.9 percent in January.

Job losses were widespread, with hefty cuts coming from construction, manufacturing, retailing, financial services and a variety of professional and business services. Those losses swamped gains elsewhere, including education and health care, leisure and hospitality and the government.

The latest snapshot of the nation's employment climate underscored the heavy toll of the housing and credit crises on companies, jobseekers and the overall economy.

To provide relief to persistent credit problems, the Federal Reserve announced Friday that it will increase the amount of loans it plans to make available to banks this month to $100 billion.

It has already provided a total of $160 billion in short-term loans to cash-strapped banks since the auctions began in December. The Fed's new step will involve making $100 billion available to a broad range of financial players through a series of separate transactions.

On Wall Street, the Dow Jones industrials were off around 15 points in morning trading as the Fed's actions helped to blunt worry about the eroding jobs situation.

The Labor report also showed that January's job losses were worse than the government first reported. Employers cut 22,000 jobs, versus 17,000.

It was the first monthly back-to-back job losses since May and June 2003, when the job market was still struggling to recover from the blows of the 2001 recession.

The health of the nation's job market is a critical factor shaping how the overall economy fares. If companies continue to cut back on hiring, that will spell more trouble.

"It certainly solidifies the notion that the economy has fallen into a recession," said Ken Mayland, economist at ClearView Economics.

Friday's report was much weaker than economists were expecting. They were forecasting employers to boost payrolls by around 25,000. However, they were also expecting the jobless rate to edge up to 5 percent. The reason why the jobless rate went down, rather than up, is because so many people stopped looking for work and left the labor force.

"We are disappointed any time you see a number showing lost jobs," Commerce Secretary Carlos Gutierrez told The Associated Press. "This is consistent with a slowdown," he said. Still, he was hopeful that the recently enacted economic stimulus package forged by the White House and Congress will help bolster the economy in the second half of this year.

Workers with jobs, however, saw modest wage gains.

Average hourly earnings for jobholders rose to $17.80 in February, a 0.3 percent increase from the previous month. That was on target with economists' forecasts. Over the last 12 months, wages were up 3.7 percent. With high energy and food prices, though, workers may feel squeezed and feel like their paychecks aren't stretching that far.

With the economy losing momentum, fears have grown that the country in on the brink of its first recession since 2001.

Economic growth slowed to a near standstill of just a 0.6 percent pace in the final quarter of last year. Many economists predict growth in the January-to-March quarter will be worse, around a 0.4 percent pace. Some believe the economy is shrinking now.

Spreading fallout from the housing and credit debacles are the main factors behind the economic slowdown. People and businesses alike are feeling the strains and have turned cautious. Adding to the stresses on pocketbooks, budgets and the economy: skyrocketing energy prices. Oil prices have set a string of record highs in recent days. Gasoline prices have marched higher, too.

To help shore up the economy, Federal Reserve Chairman Ben Bernanke signaled last week that the central bank is prepared to lower interest rates again. Economists predict another cut on March 18, the Fed's next meeting. The Fed, which has been slicing the rate since September, recently turned more forceful. It slashed the rate by 1.25 percentage points in the course of just eight days in January ? the biggest one-month reduction in a quarter century.

The White House and Congress, meanwhile, speedily enacted an economic relief package, including tax rebates for people and tax breaks for businesses. That ? along with the Fed's rate cuts ? should help give a lift to the economy in the second half of this year, says Bernanke.

Still, unemployment is expected to move higher this year. The Federal Reserve predict the jobless rate will rise to as high as 5.3 percent in 2008. Last year, the unemployment rate averaged 4.6 percent.

All the economy's troubles are putting people in a gloomy mood.

According to the RBC Cash Index, confidence sank to a mark of 33.1 in early March, the worst reading since the index began in 2002.

Thursday, March 6, 2008

Homeowner Equity Is Lowest Since 1945

Something to consider as you read this article: Is capitalism on the skids to oblivion? If so, how many people will be hurt as it goes down?

Homeowner Equity Is Lowest Since 1945

Mar 6, 2:15 PM (ET) Associated Press

By J.W. ELPHINSTONE

Homes are advertised for sale at discounted prices. Home foreclosures soared to an all-time high in the final quarter of last year and are likely to keep on rising, underscoring the suffering of distressed homeowners and the growing danger the housing meltdown poses for the economy.

NEW YORK (AP) - Americans' percentage of equity in their homes fell below 50 percent for the first time on record since 1945, the Federal Reserve said Thursday.

Homeowners' portion of equity slipped to downwardly revised 49.6 percent in the second quarter of 2007, the central bank reported in its quarterly U.S. Flow of Funds Accounts, and declined further to 47.9 percent in the fourth quarter - the third straight quarter it was under 50 percent.

That marks the first time homeowners' debt on their houses exceeds their equity since the Fed started tracking the data in 1945.

The total value of equity also fell for the third straight quarter to $9.65 trillion from a downwardly revised $9.93 trillion in the third quarter.

Home equity, which is equal to the percentage of a home's market value minus mortgage-related debt, has steadily decreased even as home prices jumped earlier this decade due to a surge in cash-out refinances, home equity loans and lines of credit and an increase in 100 percent or more home financing.

Economists expect this figure to drop even further as declining home prices eat into the value of most Americans' single largest asset.

Moody's Economy.com estimates that 8.8 million homeowners, or about 10.3 percent of homes, will have zero or negative equity by the end of the month. Even more disturbing, about 13.8 million households, or 15.9 percent, will be "upside down" if prices fall 20 percent from their peak.

The latest Standard & Poor's/Case-Shiller index showed U.S. home prices plunging 8.9 percent in the final quarter of 2007 compared with a year ago, the steepest decline in the 20-year history of the index.

The news follows a report from the Mortgage Bankers Association on Thursday that home foreclosures skyrocketed to an all-time high in the final quarter of last year. The proportion of all mortgages nationwide that fell into foreclosure surged to a record of 0.83 percent, while the percentage of adjustable-rate mortgages to borrowers with risky credit that entered the foreclosure process soared to a record of 5.29 percent.

Experts expect foreclosures to rise as more homeowners struggle with adjusting rates on their mortgages, making their monthly payments unaffordable. Problems in the credit markets and eroding home values are making it harder to refinance out of unmanageable loans.

The threat of so-called "mortgage walkers," or homeowners who can afford their payments but decide not to pay, also increases as home values depreciate and equity diminishes. Banks and credit-rating agencies already are seeing early evidence of this.

On Tuesday, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke suggested lenders reduce loan amounts to provide relief to beleaguered homeowners.

Homeowner Equity Is Lowest Since 1945

Mar 6, 2:15 PM (ET) Associated Press

By J.W. ELPHINSTONE

Homes are advertised for sale at discounted prices. Home foreclosures soared to an all-time high in the final quarter of last year and are likely to keep on rising, underscoring the suffering of distressed homeowners and the growing danger the housing meltdown poses for the economy.

NEW YORK (AP) - Americans' percentage of equity in their homes fell below 50 percent for the first time on record since 1945, the Federal Reserve said Thursday.

Homeowners' portion of equity slipped to downwardly revised 49.6 percent in the second quarter of 2007, the central bank reported in its quarterly U.S. Flow of Funds Accounts, and declined further to 47.9 percent in the fourth quarter - the third straight quarter it was under 50 percent.

That marks the first time homeowners' debt on their houses exceeds their equity since the Fed started tracking the data in 1945.

The total value of equity also fell for the third straight quarter to $9.65 trillion from a downwardly revised $9.93 trillion in the third quarter.

Home equity, which is equal to the percentage of a home's market value minus mortgage-related debt, has steadily decreased even as home prices jumped earlier this decade due to a surge in cash-out refinances, home equity loans and lines of credit and an increase in 100 percent or more home financing.

Economists expect this figure to drop even further as declining home prices eat into the value of most Americans' single largest asset.

Moody's Economy.com estimates that 8.8 million homeowners, or about 10.3 percent of homes, will have zero or negative equity by the end of the month. Even more disturbing, about 13.8 million households, or 15.9 percent, will be "upside down" if prices fall 20 percent from their peak.

The latest Standard & Poor's/Case-Shiller index showed U.S. home prices plunging 8.9 percent in the final quarter of 2007 compared with a year ago, the steepest decline in the 20-year history of the index.

The news follows a report from the Mortgage Bankers Association on Thursday that home foreclosures skyrocketed to an all-time high in the final quarter of last year. The proportion of all mortgages nationwide that fell into foreclosure surged to a record of 0.83 percent, while the percentage of adjustable-rate mortgages to borrowers with risky credit that entered the foreclosure process soared to a record of 5.29 percent.

Experts expect foreclosures to rise as more homeowners struggle with adjusting rates on their mortgages, making their monthly payments unaffordable. Problems in the credit markets and eroding home values are making it harder to refinance out of unmanageable loans.

The threat of so-called "mortgage walkers," or homeowners who can afford their payments but decide not to pay, also increases as home values depreciate and equity diminishes. Banks and credit-rating agencies already are seeing early evidence of this.

On Tuesday, Fed Chairman Ben Bernanke suggested lenders reduce loan amounts to provide relief to beleaguered homeowners.

Monday, March 3, 2008

Is a Lean Economy Turning Mean?

Is a Lean Economy Turning Mean?

The New York Times

By PETER S. GOODMAN

Published: March 2, 2008

OAKLAND, Calif. — NICOLE FLENNAUGH has a college degree, office experience and the modest expectation that, somewhere in this city on the eastern lip of San Francisco Bay, someone will want to hire her.

Nicole Flennaugh, a college graduate, has had a difficult time finding a full-time job nearly two years after she was laid off as a customer service representative.

Greg Bailey of Oakland enrolled in a biotech training program, but he has not been able to find a job in the industry.

But Ms. Flennaugh, 36, a widow, cannot secure steady, decent-paying work to support herself and her two daughters. Nearly two years after she was laid off as a customer service representative at the Educational Testing Service, and even after applying for dozens of full-time jobs, she has been getting by with occasional stints as an office temp.

“You’re used to making $17 an hour with benefits, and now you have to take any job for $8 an hour,” Ms. Flennaugh says. On a recent afternoon, she sat in front of a computer terminal at an employment center in a gritty part of town, scrolling dejectedly through online job listings while sending another batch of applications into the ether.

“I’ve literally sat and cried, but my friends with double degrees are doing worse,” she says. “It’s the economy. It’s really bad.”

Now, it’s getting tougher — particularly for those at the lower rungs of the economic ladder, and especially for African-Americans like Ms. Flennaugh. As the economy slows and perhaps slides deeper into a recession that may already be under way, communities like this — cities that have long struggled with a shortage of jobs — see work becoming scarcer still.

Across the nation, the labor market has been deteriorating. Many companies, long reluctant to add workers, are hunkered down and waiting for improved prospects, engaged in what Ed McKelvey, a senior economist at Goldman Sachs, calls “a hiring strike.” Americans with jobs are taking cuts to their work hours; those without jobs are staying out of work longer, or accepting positions that pay far less than they earned previously.

Teenagers are struggling to land minimum-wage jobs at fast-food restaurants, because those positions are increasingly being filled by adults. And those with poor credit are finding that this can disqualify them from getting a job.

IN many communities, dreams of upward mobility are yielding to despair and the grim realization that the economy — not strong for less-educated workers even when it was growing — may now be shrinking, making it tougher than ever to find a job.

Indeed, the increasingly anemic job market comes on the heels of six years of economic expansion that delivered robust corporate profits but scant job growth. The last recession, in 2001, was followed by a so-called jobless recovery. As the economy resumed growing, payrolls continued to shrink.

Even as job growth accelerated in 2005 and 2006 before slowing last year, it was not enough to return the country to its previous level. Some 62.8 percent of all Americans age 16 and older were employed at the end of last year, down from the peak of 64.6 percent in early 2000, according to the Labor Department.

“The economy never got its groove back after the tech bubble burst,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Economy.com. “We’re still feeling fallout from the collapse of the tech economy and the accounting scandals. There are still psychological scars for the managers affected. Managers are less interested in taking risks.”

In many metropolitan areas, overall employment remains below levels reached before the last recession; the list includes New York, Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee and Buffalo, as well as Boulder, Colo.; Spartanburg, S.C.; and Topeka, Kan., according to Economy.com.

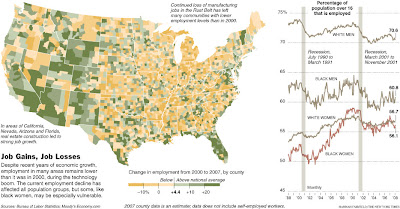

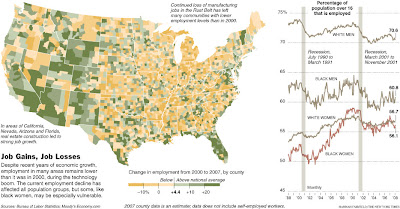

Please click on image to enlarge to read...

As the presidential contenders Hillary Rodham Clinton and Barack Obama crisscross Ohio ahead of its Democratic primary on Tuesday, they are stopping in many cities on that list — Canton, Cleveland, Dayton, Toledo. They are focusing on bread-and-butter economic issues, promising to increase the minimum wage, extend unemployment benefits and generate new jobs.

Oakland, long known as the blue-collar sibling to the aristocratic San Francisco across the bay, is among the metropolitan areas that never fully recovered from the last recession, with fewer jobs today than in March 2001, according to Economy.com. The technology boom of the 1990s and the real estate bonanza of more recent years created fewer jobs and less wealth here than they did in the moneyed enclaves like Silicon Valley. Yet if Oakland missed out on the festivities, it is already feeling the pullback.

“There’s more competition for every job,” said Gay Plair Cobb, chief executive of the Oakland Private Industry Council, a job training organization. “People are getting discouraged and depressed.”

Home to about 400,000 people, Oakland is enormously diverse, with blacks making up 36 percent of the population, Hispanics 22 percent and Asian-Americans 15 percent, according to the 2000 census. The city is racked by stubborn poverty, with one-fifth of all households living on less than $15,000 in annual income, according to the census.

Given that picture, Oakland reflects a national trend: The weaker labor market is especially pronounced for African-Americans, and black women in particular, a slide that has halted a quarter-century of steady gains.

From 1975 to early 2000, the percentage of African-American women who were employed jumped to 59 percent from 42 percent. Two years later, following a recession, the percentage had dropped to 55 percent. Since then, employment among African-American women has shown little change, reaching 55.7 percent at the end of 2007.

In a recent paper, the Center for Economic and Policy Research asserted that a recession in 2008 would be likely to swell the ranks of the unemployed by 3.2 million to 5.8 million, while raising the unemployment rate among black Americans to 11.3 percent to 15.5 percent, compared with 8.3 percent in 2007.

Nationally, the unemployment rate remains at a historically low level of 4.9 percent, though this does not include people who have given up looking for work.

The slide in employment is occurring at a time when jobs are more important than ever for millions of households headed by African-American women, because welfare changes in the 1990s forced many into the job market to compensate for a loss of public assistance.

“The labor market for low-income women is so poor that it’s almost a hoax,” says Randy Albelda, an economist at the University of Massachusetts in Boston.

For more than a decade, Dorothy Thomas, 49, an African-American and a mother of two, worked as an administrative assistant at various health care centers in Northern California. In her last job, she earned $16 an hour, as well as benefits, she said.

It was never enough to pay all the bills, she said, so she made choices, paying this one, not paying that one, all the while focused on one mission: getting her two daughters through school. She lived in apartments in better neighborhoods, paying more rent than she could afford to ensure that her girls attended better schools.

“I truly bought into the idea that education is the way out of poverty,” Ms. Thomas says. One daughter received a master’s degree in education and is a teacher in Hawaii, she says, and the other is still in college.

But the bills for Ms. Thomas are still coming due. She lost her car in November 2005 after she fell behind on the payments. Unable to drive to work, she lost her job. Since then, she has been unable to find a job.

Several times, she has landed interviews that seemed likely to bring offers, but the jobs required a credit check — a test she cannot pass.

“My credit is just so in shambles,” she told a classroom full of people gathered for a credit counseling session at the Private Industry Council. “More and more jobs are checking your credit. They’re saying that credit is a reflection of your character.”

Ms. Thomas deftly toggles between different modes of speech, from street-smart to receptionist-smooth. But getting to work without transportation and buying clothes for interviews without cash are beyond her abilities.

“Why can’t I get a job?” she asks, her eyes welling with tears. “Is it because of my age? Is it because I’ve gained weight? I’m articulate. I’m a positive thinker. I know how to conduct myself in an office setting. But I’m starting to lose all my confidence.”

Government data show that the labor market has weakened in recent years for nearly every demographic group. Women as well as men; whites, blacks, Hispanics and Asian-Americans; teenagers and the middle-aged; high school graduates and those with college degrees. In terms of employment as a percentage of population, all remain below the level reached before the last recession.

The source of this weakening and what it says about the overall, long-term health of the economy are the subject of fractious debate.

Some economists argue that the labor market has merely settled back to earth after years of ridiculously aggressive investment in technology, which created far more jobs in the 1990s than could be sustained.

“This is a return to normal,” says Robert E. Hall, an economist and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, a conservative research group at Stanford.

But others conclude that the sluggish job market reflects long-term, systemic forces reshaping the American economy. It represents, they say, the underbelly of the so-called new moderation that has made recessions less frequent and less severe.

Traditionally, the American economy has often expanded in extreme cycles. In periods of growth, companies hire aggressively. When they sense a slowdown, they cut back, laying off workers and curtailing investments, amplifying the ripples of retrenchment. Now, however, companies aim to keep their work forces lean all the time.

AS the American economy boomed in the late 1990s, so did business for the Bartlett Manufacturing Company, a circuit-board maker based in Cary, Ill. By 2000, it had about 200 workers — mostly in blue-collar assembly jobs at its original factory near Chicago, and an additional 50 or so at a new plant in Albuquerque, said the company’s chairman, Douglas S. Bartlett. Most of the positions paid $10 to $11 an hour.

But by late 2001, with the country in recession and many orders flowing to China, business was down two-thirds from the best years. So the company shuttered its Albuquerque factory and laid off more than 100 workers at its Chicago plant, bringing its total work force down to 87.

Business improved slightly in 2004 and 2005 and remained essentially flat over the last two years, but the company hasn’t added workers.

“We improved our process through automation,” Mr. Bartlett says.

If business now deteriorates, he does not expect to shed workers, because he is already down to the minimum needed to keep his plant running.

“When a customer calls, you need to be able to deliver parts in three or four days because, if they could wait longer, they would just go offshore and get it cheaper,” Mr. Bartlett says. “We don’t lay people off at this point. We just reduce hours. We pretty much can’t get any leaner.”

Bartlett Manufacturing’s experience is emblematic of forces at work throughout the economy. An anemic job market is not so much a product of layoffs — which remain relatively few — as it is a result of a sharp pullback in hiring.

In 1994, 30 million people were hired into new and existing private-sector jobs, according to the Labor Department. By 2000, the number of hires had expanded to 34 million. A year later, in the midst of the recession, hiring slackened to 31.6 million, while layoffs winnowed the work force.

In 2003, with the economy again growing, layoffs slowed, but the private sector hired only 29.8 million — a figure that has nudged up only a little in the years since.

Rather than hire and risk having to fire in another downturn, companies added hours for those already on the payroll and relied more on temporary workers, said Mr. McKelvey, the Goldman Sachs economist. Manufacturing companies continued to automate, to squeeze more production out of the same number of workers, while shifting jobs to lower-cost countries like China and Mexico. For lower-skilled workers, that intensifies the competition for the jobs that remain.

“Now, you’re not only competing against the guy next door,” Mr. McKelvey says. “You’re competing against the guy across the water.”

Some economists say the weakness of hiring in recent years may protect those with jobs against the usual impact of a recession: Many companies are so lean that the unemployment rate may not increase much.

“It’s not your grandfather’s recession anymore,” says Jared Bernstein, senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute, a labor-oriented research group in Washington. “You’re probably going to see fewer layoffs, because you just don’t have the traditional model.”

But the same trend suggests that the impacts of the slowdown are likely to be felt deeply for several years, even after the economy resumes a swift expansion, Mr. Bernstein added.

Before 1990, it took an average of 21 months for the economy to add back the jobs shed during a recession, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute and the National Employment Law Project, a worker advocacy group. Yet in the last two recessions, in 1990 and 2001, it took 31 months and 46 months, respectively, for employment levels to recover fully.

In the recessions of the early 1980s and the early 1990s, the ranks of the so-called long-term unemployed — those out of work for 27 weeks or more — jumped to well above 20 percent of all unemployed people. But in both cases, that share eventually settled back to close to 10 percent of the unemployed.

After the 2001 recession, however, the long-term share stayed above 20 percent from the fall of 2002 until the spring of 2005. In the months since, it has never dipped below 16 percent. In January, 18 percent of those unemployed had been without work for at least 27 weeks, according to the Labor Department.

OAKLAND is typical of the lean hiring that has accompanied the winnowing of jobs. In recent decades, Oakland’s once-formidable manufacturing base has hollowed out as the city has lost food processing factories, auto plants and warehouses. Downtown, concrete-floor factories have been turned into chic residential loft spaces.

Yet the Port of Oakland is booming, with dozens of cranes arrayed at the bay’s edge, plucking containers full of cars and electronic products off of ships arriving from Asia, and depositing shipments of produce from the Central Valley of California.

The port has benefited from a surge in American exports. Port officials cite an economic development study showing that jobs connected in some way to their operations — in industries ranging from cargo and trucking to insurance and retail — doubled to more than 28,000 from 2001 to 2005. A planned $800 million expansion would add 7,000 more jobs, said James Kwon, director of the port’s maritime division.

Deborah Acosta, international trade project manager of the Community and Economic Development Agency of Oakland, says, “We’re talking about good-paying jobs that don’t require a college degree.”

So far, the growth at the port has not been enough to compensate for steady erosion of work elsewhere in the city. Since 2001, the metropolitan area has shed 22,000 manufacturing jobs, and thousands more in transportation and warehousing, and professional and business services, according to Economy.com.

For public officials grappling with the social and political impact of long-term joblessness, training has become a mantra.

“The jobs are there, but the people to fill the jobs are not,” says John Garamendi, the lieutenant governor of California. “The current demand for skilled individuals in medical fields, in biotech, for people capable of welding — there’s a demand for these people.”

But all too often, these job-training programs fail to find people the jobs they expect, said Marsha Murrington, vice president for programs at the Unity Council, a nonprofit social service organization that operates a job center in Oakland.

“People are getting training or high degrees in areas that are not supported by the job market,” she complains. “People are looking for those high-paying corporate jobs that aren’t there.”

Greg Bailey, another Oakland resident, is among those who banked on the benefits of job training. Last spring, after 15 years as a truck driver, an installer of household appliances and a warehouse stocker — jobs that left him nursing a bad back and high blood pressure — Mr. Bailey decided to pursue work that was less physically taxing. He enrolled in a government-financed training program to gain the skills needed to work at one of the many biotechnology plants sprouting up in the area.

“It sounded great; the opportunities were almost endless,” said Mr. Bailey, 40, tall, soft-spoken and personable.

A former high school basketball star, Mr. Bailey said he had to turn down several college scholarships when he graduated so he could find a job and support his mother, who was ill, along with his younger brother. Later, he enrolled several times in various college programs, but the demands of being the family’s primary breadwinner left too few hours for schoolwork.

The biotech training program was to be a way to jump ahead, putting him in position to earn $17 to $18 an hour, as well as health benefits, as a warehouse or maintenance worker in an industry that offered other chances for advancement. But despite applying for about 100 jobs over the last six months, he says, he has never been invited to an interview.

Last summer, a month after the course ended, he went to a job center in East Oakland and was surprised to bump into six of his classmates.

“I was like, ‘Oh man, you’re all here too?’ ” Mr. Bailey said. “We all started looking at anything at that point. It was kind of depressing.”

RECENTLY, he began applying for the same types of jobs from which he had hoped to escape. Now, even those jobs seem beyond reach. He did take one warehouse job that started at 5 a.m. and required him to walk two miles to and from work, but he quit in disgust after two weeks. It paid $10 an hour — two-thirds of what he used to make as a truck driver.

He applied for a minimum-wage job at Wal-Mart, but after two interviews the person doing the hiring was fired, he said, and Mr. Bailey was told that he had to start all over — this for a night shift at a store in an area plagued by crime. Disenchanted, he stopped pursuing a career at Wal-Mart.

“I’ll just look for anything now; it doesn’t matter,” he confided on a recent afternoon.

The next day, he accepted a job at a warehouse for $9 an hour.

“It’s just picking up boxes,” he says. “That’s all right. I’ve got to do something.”

The New York Times

By PETER S. GOODMAN

Published: March 2, 2008

OAKLAND, Calif. — NICOLE FLENNAUGH has a college degree, office experience and the modest expectation that, somewhere in this city on the eastern lip of San Francisco Bay, someone will want to hire her.

Nicole Flennaugh, a college graduate, has had a difficult time finding a full-time job nearly two years after she was laid off as a customer service representative.

Greg Bailey of Oakland enrolled in a biotech training program, but he has not been able to find a job in the industry.

But Ms. Flennaugh, 36, a widow, cannot secure steady, decent-paying work to support herself and her two daughters. Nearly two years after she was laid off as a customer service representative at the Educational Testing Service, and even after applying for dozens of full-time jobs, she has been getting by with occasional stints as an office temp.

“You’re used to making $17 an hour with benefits, and now you have to take any job for $8 an hour,” Ms. Flennaugh says. On a recent afternoon, she sat in front of a computer terminal at an employment center in a gritty part of town, scrolling dejectedly through online job listings while sending another batch of applications into the ether.

“I’ve literally sat and cried, but my friends with double degrees are doing worse,” she says. “It’s the economy. It’s really bad.”

Now, it’s getting tougher — particularly for those at the lower rungs of the economic ladder, and especially for African-Americans like Ms. Flennaugh. As the economy slows and perhaps slides deeper into a recession that may already be under way, communities like this — cities that have long struggled with a shortage of jobs — see work becoming scarcer still.

Across the nation, the labor market has been deteriorating. Many companies, long reluctant to add workers, are hunkered down and waiting for improved prospects, engaged in what Ed McKelvey, a senior economist at Goldman Sachs, calls “a hiring strike.” Americans with jobs are taking cuts to their work hours; those without jobs are staying out of work longer, or accepting positions that pay far less than they earned previously.

Teenagers are struggling to land minimum-wage jobs at fast-food restaurants, because those positions are increasingly being filled by adults. And those with poor credit are finding that this can disqualify them from getting a job.

IN many communities, dreams of upward mobility are yielding to despair and the grim realization that the economy — not strong for less-educated workers even when it was growing — may now be shrinking, making it tougher than ever to find a job.

Indeed, the increasingly anemic job market comes on the heels of six years of economic expansion that delivered robust corporate profits but scant job growth. The last recession, in 2001, was followed by a so-called jobless recovery. As the economy resumed growing, payrolls continued to shrink.

Even as job growth accelerated in 2005 and 2006 before slowing last year, it was not enough to return the country to its previous level. Some 62.8 percent of all Americans age 16 and older were employed at the end of last year, down from the peak of 64.6 percent in early 2000, according to the Labor Department.

“The economy never got its groove back after the tech bubble burst,” says Mark Zandi, chief economist at Moody’s Economy.com. “We’re still feeling fallout from the collapse of the tech economy and the accounting scandals. There are still psychological scars for the managers affected. Managers are less interested in taking risks.”

In many metropolitan areas, overall employment remains below levels reached before the last recession; the list includes New York, Chicago, Detroit, Milwaukee and Buffalo, as well as Boulder, Colo.; Spartanburg, S.C.; and Topeka, Kan., according to Economy.com.

Please click on image to enlarge to read...

As the presidential contenders Hillary Rodham Clinton and Barack Obama crisscross Ohio ahead of its Democratic primary on Tuesday, they are stopping in many cities on that list — Canton, Cleveland, Dayton, Toledo. They are focusing on bread-and-butter economic issues, promising to increase the minimum wage, extend unemployment benefits and generate new jobs.

Oakland, long known as the blue-collar sibling to the aristocratic San Francisco across the bay, is among the metropolitan areas that never fully recovered from the last recession, with fewer jobs today than in March 2001, according to Economy.com. The technology boom of the 1990s and the real estate bonanza of more recent years created fewer jobs and less wealth here than they did in the moneyed enclaves like Silicon Valley. Yet if Oakland missed out on the festivities, it is already feeling the pullback.

“There’s more competition for every job,” said Gay Plair Cobb, chief executive of the Oakland Private Industry Council, a job training organization. “People are getting discouraged and depressed.”

Home to about 400,000 people, Oakland is enormously diverse, with blacks making up 36 percent of the population, Hispanics 22 percent and Asian-Americans 15 percent, according to the 2000 census. The city is racked by stubborn poverty, with one-fifth of all households living on less than $15,000 in annual income, according to the census.

Given that picture, Oakland reflects a national trend: The weaker labor market is especially pronounced for African-Americans, and black women in particular, a slide that has halted a quarter-century of steady gains.

From 1975 to early 2000, the percentage of African-American women who were employed jumped to 59 percent from 42 percent. Two years later, following a recession, the percentage had dropped to 55 percent. Since then, employment among African-American women has shown little change, reaching 55.7 percent at the end of 2007.

In a recent paper, the Center for Economic and Policy Research asserted that a recession in 2008 would be likely to swell the ranks of the unemployed by 3.2 million to 5.8 million, while raising the unemployment rate among black Americans to 11.3 percent to 15.5 percent, compared with 8.3 percent in 2007.

Nationally, the unemployment rate remains at a historically low level of 4.9 percent, though this does not include people who have given up looking for work.

The slide in employment is occurring at a time when jobs are more important than ever for millions of households headed by African-American women, because welfare changes in the 1990s forced many into the job market to compensate for a loss of public assistance.

“The labor market for low-income women is so poor that it’s almost a hoax,” says Randy Albelda, an economist at the University of Massachusetts in Boston.

For more than a decade, Dorothy Thomas, 49, an African-American and a mother of two, worked as an administrative assistant at various health care centers in Northern California. In her last job, she earned $16 an hour, as well as benefits, she said.

It was never enough to pay all the bills, she said, so she made choices, paying this one, not paying that one, all the while focused on one mission: getting her two daughters through school. She lived in apartments in better neighborhoods, paying more rent than she could afford to ensure that her girls attended better schools.

“I truly bought into the idea that education is the way out of poverty,” Ms. Thomas says. One daughter received a master’s degree in education and is a teacher in Hawaii, she says, and the other is still in college.

But the bills for Ms. Thomas are still coming due. She lost her car in November 2005 after she fell behind on the payments. Unable to drive to work, she lost her job. Since then, she has been unable to find a job.

Several times, she has landed interviews that seemed likely to bring offers, but the jobs required a credit check — a test she cannot pass.

“My credit is just so in shambles,” she told a classroom full of people gathered for a credit counseling session at the Private Industry Council. “More and more jobs are checking your credit. They’re saying that credit is a reflection of your character.”

Ms. Thomas deftly toggles between different modes of speech, from street-smart to receptionist-smooth. But getting to work without transportation and buying clothes for interviews without cash are beyond her abilities.

“Why can’t I get a job?” she asks, her eyes welling with tears. “Is it because of my age? Is it because I’ve gained weight? I’m articulate. I’m a positive thinker. I know how to conduct myself in an office setting. But I’m starting to lose all my confidence.”

Government data show that the labor market has weakened in recent years for nearly every demographic group. Women as well as men; whites, blacks, Hispanics and Asian-Americans; teenagers and the middle-aged; high school graduates and those with college degrees. In terms of employment as a percentage of population, all remain below the level reached before the last recession.

The source of this weakening and what it says about the overall, long-term health of the economy are the subject of fractious debate.

Some economists argue that the labor market has merely settled back to earth after years of ridiculously aggressive investment in technology, which created far more jobs in the 1990s than could be sustained.

“This is a return to normal,” says Robert E. Hall, an economist and senior fellow at the Hoover Institution, a conservative research group at Stanford.

But others conclude that the sluggish job market reflects long-term, systemic forces reshaping the American economy. It represents, they say, the underbelly of the so-called new moderation that has made recessions less frequent and less severe.

Traditionally, the American economy has often expanded in extreme cycles. In periods of growth, companies hire aggressively. When they sense a slowdown, they cut back, laying off workers and curtailing investments, amplifying the ripples of retrenchment. Now, however, companies aim to keep their work forces lean all the time.

AS the American economy boomed in the late 1990s, so did business for the Bartlett Manufacturing Company, a circuit-board maker based in Cary, Ill. By 2000, it had about 200 workers — mostly in blue-collar assembly jobs at its original factory near Chicago, and an additional 50 or so at a new plant in Albuquerque, said the company’s chairman, Douglas S. Bartlett. Most of the positions paid $10 to $11 an hour.

But by late 2001, with the country in recession and many orders flowing to China, business was down two-thirds from the best years. So the company shuttered its Albuquerque factory and laid off more than 100 workers at its Chicago plant, bringing its total work force down to 87.

Business improved slightly in 2004 and 2005 and remained essentially flat over the last two years, but the company hasn’t added workers.

“We improved our process through automation,” Mr. Bartlett says.

If business now deteriorates, he does not expect to shed workers, because he is already down to the minimum needed to keep his plant running.

“When a customer calls, you need to be able to deliver parts in three or four days because, if they could wait longer, they would just go offshore and get it cheaper,” Mr. Bartlett says. “We don’t lay people off at this point. We just reduce hours. We pretty much can’t get any leaner.”

Bartlett Manufacturing’s experience is emblematic of forces at work throughout the economy. An anemic job market is not so much a product of layoffs — which remain relatively few — as it is a result of a sharp pullback in hiring.

In 1994, 30 million people were hired into new and existing private-sector jobs, according to the Labor Department. By 2000, the number of hires had expanded to 34 million. A year later, in the midst of the recession, hiring slackened to 31.6 million, while layoffs winnowed the work force.

In 2003, with the economy again growing, layoffs slowed, but the private sector hired only 29.8 million — a figure that has nudged up only a little in the years since.

Rather than hire and risk having to fire in another downturn, companies added hours for those already on the payroll and relied more on temporary workers, said Mr. McKelvey, the Goldman Sachs economist. Manufacturing companies continued to automate, to squeeze more production out of the same number of workers, while shifting jobs to lower-cost countries like China and Mexico. For lower-skilled workers, that intensifies the competition for the jobs that remain.

“Now, you’re not only competing against the guy next door,” Mr. McKelvey says. “You’re competing against the guy across the water.”

Some economists say the weakness of hiring in recent years may protect those with jobs against the usual impact of a recession: Many companies are so lean that the unemployment rate may not increase much.

“It’s not your grandfather’s recession anymore,” says Jared Bernstein, senior economist at the Economic Policy Institute, a labor-oriented research group in Washington. “You’re probably going to see fewer layoffs, because you just don’t have the traditional model.”

But the same trend suggests that the impacts of the slowdown are likely to be felt deeply for several years, even after the economy resumes a swift expansion, Mr. Bernstein added.

Before 1990, it took an average of 21 months for the economy to add back the jobs shed during a recession, according to an analysis by the Economic Policy Institute and the National Employment Law Project, a worker advocacy group. Yet in the last two recessions, in 1990 and 2001, it took 31 months and 46 months, respectively, for employment levels to recover fully.

In the recessions of the early 1980s and the early 1990s, the ranks of the so-called long-term unemployed — those out of work for 27 weeks or more — jumped to well above 20 percent of all unemployed people. But in both cases, that share eventually settled back to close to 10 percent of the unemployed.

After the 2001 recession, however, the long-term share stayed above 20 percent from the fall of 2002 until the spring of 2005. In the months since, it has never dipped below 16 percent. In January, 18 percent of those unemployed had been without work for at least 27 weeks, according to the Labor Department.

OAKLAND is typical of the lean hiring that has accompanied the winnowing of jobs. In recent decades, Oakland’s once-formidable manufacturing base has hollowed out as the city has lost food processing factories, auto plants and warehouses. Downtown, concrete-floor factories have been turned into chic residential loft spaces.

Yet the Port of Oakland is booming, with dozens of cranes arrayed at the bay’s edge, plucking containers full of cars and electronic products off of ships arriving from Asia, and depositing shipments of produce from the Central Valley of California.

The port has benefited from a surge in American exports. Port officials cite an economic development study showing that jobs connected in some way to their operations — in industries ranging from cargo and trucking to insurance and retail — doubled to more than 28,000 from 2001 to 2005. A planned $800 million expansion would add 7,000 more jobs, said James Kwon, director of the port’s maritime division.

Deborah Acosta, international trade project manager of the Community and Economic Development Agency of Oakland, says, “We’re talking about good-paying jobs that don’t require a college degree.”

So far, the growth at the port has not been enough to compensate for steady erosion of work elsewhere in the city. Since 2001, the metropolitan area has shed 22,000 manufacturing jobs, and thousands more in transportation and warehousing, and professional and business services, according to Economy.com.

For public officials grappling with the social and political impact of long-term joblessness, training has become a mantra.

“The jobs are there, but the people to fill the jobs are not,” says John Garamendi, the lieutenant governor of California. “The current demand for skilled individuals in medical fields, in biotech, for people capable of welding — there’s a demand for these people.”

But all too often, these job-training programs fail to find people the jobs they expect, said Marsha Murrington, vice president for programs at the Unity Council, a nonprofit social service organization that operates a job center in Oakland.

“People are getting training or high degrees in areas that are not supported by the job market,” she complains. “People are looking for those high-paying corporate jobs that aren’t there.”

Greg Bailey, another Oakland resident, is among those who banked on the benefits of job training. Last spring, after 15 years as a truck driver, an installer of household appliances and a warehouse stocker — jobs that left him nursing a bad back and high blood pressure — Mr. Bailey decided to pursue work that was less physically taxing. He enrolled in a government-financed training program to gain the skills needed to work at one of the many biotechnology plants sprouting up in the area.

“It sounded great; the opportunities were almost endless,” said Mr. Bailey, 40, tall, soft-spoken and personable.

A former high school basketball star, Mr. Bailey said he had to turn down several college scholarships when he graduated so he could find a job and support his mother, who was ill, along with his younger brother. Later, he enrolled several times in various college programs, but the demands of being the family’s primary breadwinner left too few hours for schoolwork.

The biotech training program was to be a way to jump ahead, putting him in position to earn $17 to $18 an hour, as well as health benefits, as a warehouse or maintenance worker in an industry that offered other chances for advancement. But despite applying for about 100 jobs over the last six months, he says, he has never been invited to an interview.

Last summer, a month after the course ended, he went to a job center in East Oakland and was surprised to bump into six of his classmates.

“I was like, ‘Oh man, you’re all here too?’ ” Mr. Bailey said. “We all started looking at anything at that point. It was kind of depressing.”

RECENTLY, he began applying for the same types of jobs from which he had hoped to escape. Now, even those jobs seem beyond reach. He did take one warehouse job that started at 5 a.m. and required him to walk two miles to and from work, but he quit in disgust after two weeks. It paid $10 an hour — two-thirds of what he used to make as a truck driver.

He applied for a minimum-wage job at Wal-Mart, but after two interviews the person doing the hiring was fired, he said, and Mr. Bailey was told that he had to start all over — this for a night shift at a store in an area plagued by crime. Disenchanted, he stopped pursuing a career at Wal-Mart.

“I’ll just look for anything now; it doesn’t matter,” he confided on a recent afternoon.

The next day, he accepted a job at a warehouse for $9 an hour.

“It’s just picking up boxes,” he says. “That’s all right. I’ve got to do something.”

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)